At the 22nd Biennial Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM), held June 12–15, 2025, at Brunel University London, Ed Timke, Ph.D. — Assistant Professor of Advertising and Public Relations — and Christina L. Myers, Ph.D. — Assistant Professor of Journalism — brought critical insight to a campaign that once delighted audiences — and now invites more complex reflection.

Their presentation, “Consuming Black Culture: The Materiality and Cultural Exploitation of the California Raisins Campaign,” highlighted how a beloved advertising phenomenon intersected with questions of cultural appropriation, commercial exploitation, and representation.

Recently, Timke was nominated and elected to the CHARM Board of Directors. Here, Timke, a public cultural historian of advertising, and Myers, a scholar of race and media, reflect on their research, their experience presenting at CHARM, and what’s next for their collaborative exploration of race, advertising, and cultural history.

Q: What initially stood out to you both about this specific advertising campaign, and what do you find most compelling about the topic?

Timke: I was enamored with the California Raisins as a child in the late 1980s. I loved the Motown sound, the dancing, and the overall cool factor, even though I didn’t like raisins! However, as I got older, I began to question how those images may have shaped my understanding of Black culture.

Myers: Same here. My first memory is just being a kid and thinking how amazing it was to see animated characters performing music I grew up hearing in my household. But now, as a scholar, I see this tension between innovation and appropriation. While it was brilliant storytelling and cultural marketing, it raises important questions about how Black culture, especially Motown and soul, has been borrowed or repackaged without honoring its roots. That complexity is what makes this campaign so compelling to study.

Q: What were some of the key points of the research featured in your presentation?

Timke: This is an archival project with many layers. We consulted the Will Vinton Archive at the Academy of Motion Pictures — Vinton being a pioneer of Claymation — and combined that with materials from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. We also gathered figurines and ephemera from eBay, antique shops, and digital sources. A major part of our work is tracing how this campaign was created, how it evolved, and how its materiality shaped cultural perception.

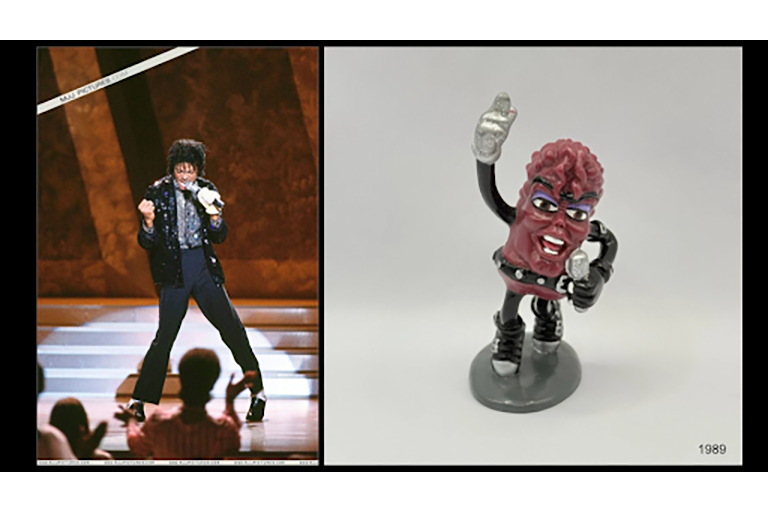

Myers: Exactly, and we dig into the deeper meanings — whether this was appropriation, exploitation, or celebration. We explore how white ad executives profited off a stylized representation of Black culture. One of our key arguments is that the campaign invited consumers, especially children, to consume Blackness metaphorically and materially. That’s why we examine both the literal marketing objects and their symbolic implications.

Q: How did the public receive the imagery associated with the campaign at the time? Around what point in time did the campaign begin to receive backlash?

Timke: There was no significant backlash at the time. In fact, it was actually incredibly popular. The merchandise was everywhere, from Hardee’s figurines to catalogs. The California Raisin Advisory Board used it to revitalize a stagnant market. Criticism was minimal in mainstream media. But today, Gen Z audiences are questioning the imagery. So, while backlash wasn’t immediate, there’s a growing critique as people look back. And yet, it’s important to note that even now, the campaign is included on the current website marketing raisins from California, so the raisins haven’t gone away from usage in some instances.

Myers: Yes, public memory often recalls the California Raisins with nostalgia, but critical cultural study scholars like would situate these characters within a longer tradition of racial caricature and commercialized stereotypes. These figures are not anomalies—they are part of a broader pattern in which Black cultural aesthetics are repackaged for mainstream consumption while reinforcing familiar tropes about race, performance and entertainment.

Q: What are the wider cultural implications of the California Raisins Campaign? What are some ways it still bears relevance today?

Myers: This campaign was groundbreaking in how it used animation and nostalgic music to create a powerful brand personality, but it also relied heavily on stereotypical caricatures of Black culture — soulful singing, exaggerated features, and stylized dancing that evoke minstrel imagery. While beloved by many, the campaign illustrates how Black cultural expression has often been commodified without context or representation. It reminds us how important it is today to ask who gets to tell their stories, and how culture is packaged for consumption.

Timke: The subtlety of the campaign’s racial messaging is what made it so pervasive and potentially harmful. People didn’t necessarily recognize the harm because the imagery was fun, catchy, and seemingly harmless.

Myers: That’s why we used critical race theory to understand how racism can be normalized in everyday media. We wanted to show how cultural symbols like the Raisins impact both how communities see themselves and how others see them.

Q: When presenting research at an interactive conference such as CHARM, what does the process of preparing an engaging presentation look like?

Timke: Because our project focused on material culture, we made our presentation experiential. We brought actual objects, such as figurines, ads, memorabilia, and kept our slides light on text. We showed a lot of media and let the visuals speak. We also spoke from the heart and went back and forth conversationally to keep the energy alive.

Myers: That format really reflected who we are as teachers and scholars. We wanted the presentation to be interactive and relatable. The concepts can be complex, but they’re grounded in everyday culture. Our goal was to make media history feel immediate and meaningful.

Q: Looking ahead, what are some areas of research you would be interested in exploring?

Timke: Our California Raisins project definitely has legs. There’s so much more to uncover! We’re developing an article, but many colleagues have encouraged us to turn it into a book. So, we’re thinking about that.

Myers: Yes, and we won’t give too much away just yet, but we’re excited about the possibilities ahead!