Scholars in the Center for Avatar Research and Immersive Social Media Applications (CARISMA) Lab at Michigan State University are pioneering interdisciplinary research to study basic social-communicative processes within immersive environments.

From theory to innovation: how MSU’s CARISMA Lab is leading XR research

Nestled beneath ComArtSci, the CARISMA Lab stands at the cutting edge of extended reality (XR) research. Since opening in 2016, the lab’s interdisciplinary team, led by Professor Gary Bente, is redefining how we perceive and interact within immersive environments, pushing the boundaries of communication science.

For Bente, this methodology began long before the Oculus Rift or the Meta Quest. Bente has been blazing the XR trail since the 1980s, publishing his first article on using 3-D animation to study nonverbal communication in Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers in 1989, and continuing throughout the ‘90s. He published his first book “Virtuelle Realitäten” covering virtual reality from a psychological perspective in 2002. Seventeen years later, editors S.W. Wilson and S.W. Smith published Bente’s chapter on using emergent technologies in nonverbal communication research in their book “Reflections on Interpersonal Communication” (2019). In this chapter, Bente details the experiments that inspired him to use avatars to begin with — and how, over time, technological advancements enabled him to collect even better, more precise data.

“The biggest challenge for research in natural sciences and hard science is to recreate nature, to simulate what’s going on,” Bente said. “So, if you were able to recreate a phenomenon by just numbers and getting an animation on the screen, for example — then you have understood what’s going on, I guessed.”

Bente began using his descriptive, coded data to produce those animations and simple wire frame models himself. “I was always expecting ... this will fly,” he said. “Avatars and agents, this will be the future. Nobody believed me.”

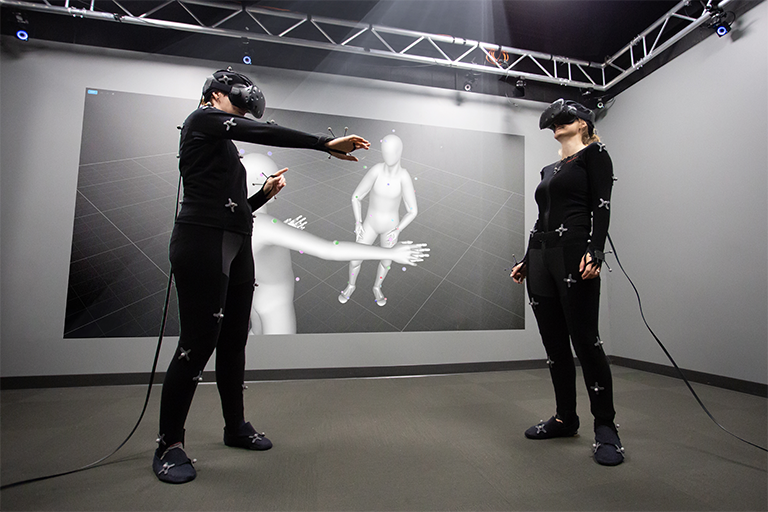

Photo: Animations are created in the CARISMA Lab using motion capture suits and computer programming.

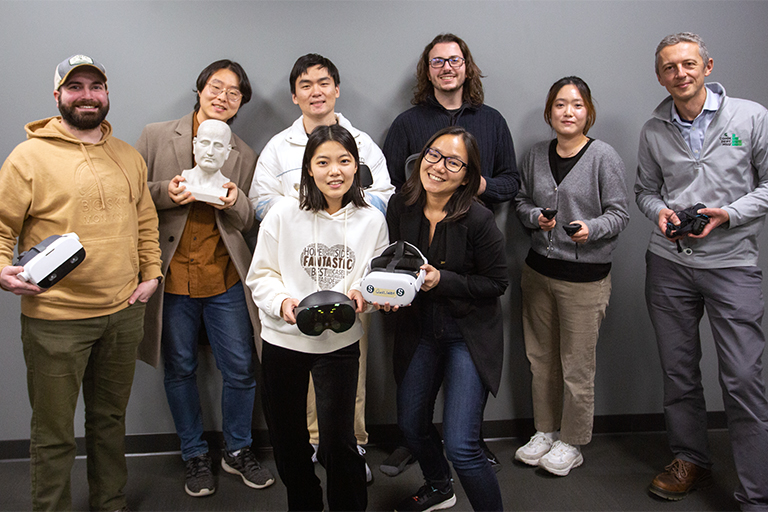

Today, CARISMA Lab’s research spans several critical areas — including nonverbal communication, communication neuroscience and media psychology — gleaning profound insights into human behavior by using advanced technologies like motion capture, electroencephalogram (EEG) systems, VR headsets and more.

CARISMA Lab’s co-director, Associate Professor Ralf Schmälzle, is a cognitive neuroscientist using XR technologies to study things that are otherwise difficult to analyze, particularly in the realm of social interactions.

“There is one theory that has a strong history in MSU; it’s called expectancy violation theory,” Schmälzle said. This theory seeks to explain how people respond when others behave in a way that doesn’t align with their expectations or social norms, which happens regularly in social interaction. “There are these little micro disturbances, and then the brain rings kind of an alarm bell — and one can ideally study that in virtual contexts.”

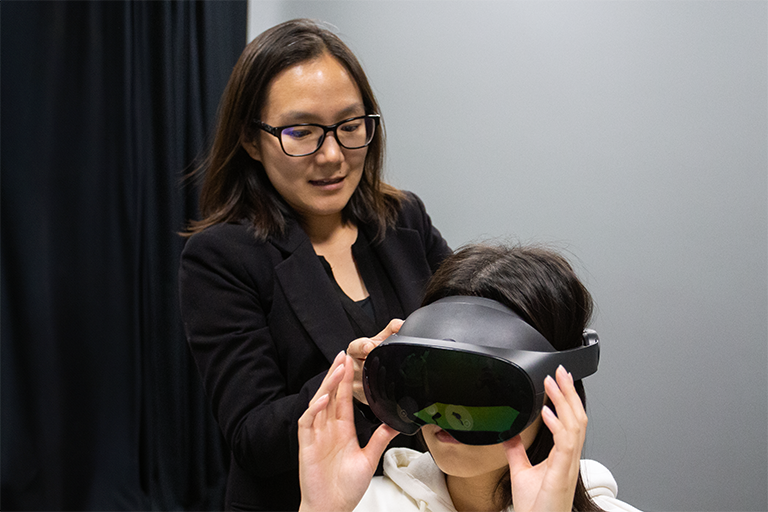

Photo: Ralf Schmälzle facilitates an XR experience for MSU President Kevin Guskiewicz during his visit to CARISMA Lab.

Schmälzle says a benefit of using virtual reality (VR) headsets is that participants can have natural interactions with other people and the neurophysiological measurement gear is already wrapped around their head.

“We’re interested in the eye. The eye is the main information acquisition device that the brain has,” he said. “The majority of information that comes into the brain goes in either via the eye or via the ear, and those are also the two senses that VR can best already capture — because VR is basically just a cell phone in front of your eyes.”

As eye tracking has become more integrated in standard VR headsets, this tool is both accessible and invaluable to cognitive neuroscientists like Schmälzle. In one of CARISMA’s recent projects, the team used VR to track how our eyes react to media content in real-time. By observing tiny changes in pupil size, the researchers could measure audience engagement and emotional responses with a level of unprecedented accuracy. This methodology could revolutionize how we tailor media content to better connect with viewers, whether in traditional media or in emerging virtual environments.

CARISMA researchers aren’t only interested in how people react to media; they also explore how our surroundings influence what we notice and remember. The VR Billboard Paradigm study is a perfect example. By recreating a roadside environment in VR, researchers can measure where people look and what they remember when exposed to advertising — providing valuable insights into how to craft more effective visual communication strategies in the real world, as well as implications for road safety.

Sue Lim is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Communication with an interest in combining artificial intelligence (AI) and VR methods. As a laboratory assistant at CARISMA, Lim regularly works with Bente and Schmälzle. For one of her latest studies examining how interactions with AI agents can subtly influence human behavior, the CARISMA researchers built embodied conversational agents, called VR-ECAs, that can naturally converse with humans. The study revealed that when the gender of AI agents did not match that of the participants, engagement in health-related conversations and decision-making improved. It also found participants experienced greater presence while conversing with VR-embodied agents than while chatting with text-only agents, like Chat GPT. This study paves the way for new experimental research — highlighting how the way AI is presented can shape human interactions, with potential applications in education, healthcare and more.

Photos: Sue Lim assists with putting on the VR headset and views what the participant is able to see.

“If you use avatars for research, the basic question is: is it the same as if you would use real people, or a video of real people?” Bente said. It’s a question he has put to the test many times with a variety of experiments. Each time, the results were nearly identical.

“Nonverbal behavior is also about using space. If you move forward in the space, you invade a little bit more of my space; the co-presence might be something that makes a difference,” Bente explained. “I wanted to see whether if I observe somebody expressing an emotion in a shared space — or the same person showing this emotion on the screen, for example — does this make a difference?”

To test that, Bente’s research on emotion perception in shared virtual environments explored how being in the same virtual space as others affects our emotional judgments. The researchers found subtle differences, but the attributions participants made, the hit rates for emotions, were still the same.

One area that can benefit from this insight, Schmälzle says, is virtual meeting platforms (like Zoom, Teams or Skype) since both spatial and social presence are key in shaping social interactions and emotional experiences. “You have a sort of spatial presence right now [in a virtual meeting]; you are a 2D face on the screen and we can have a conversation because a lot of it works via verbal information exchange,” he said. “Some social presence is also there, but I would argue it’s only about 10% compared to what the real thing is.”

Schmälzle and Bente (as well as colleagues at the SPARTIE Lab) believe that virtual meetings, held in virtual reality, will be an improvement to what we currently experience … at least, once the animations are able to translate the full range of expressive body postures and facial movements with high fidelity.

“I think in the end it will be super realistic so that you really cannot make the distinction,” Bente said.

“But I think what’s really coming — and 20 years ago, I said this will be the world: where we have augmented reality, the other is coming in as an avatar and taking a seat on my real couch — well, that’s it.”

By Jessica Mussell

CARISMA Lab research

Basic research:

CARISMA uses XR technology as a methodology to study the basics of human communication and nonverbal interaction. Motion capture, neurophysiological measures and avatar animations provide new insights into the bio-behavioral mechanisms underlying person perception, emotion inferences, conflict management and social bonding.

Applied Research:

In collaboration with media industry partners, CARISMA helps to develop and evaluate practical XR applications for entertainment, training and therapy. We study user responses and outcomes of XR usage along a variety of cognitive, emotional and behavioral measures, including enjoyment, stress, learning and more.

If you are interested in our research, please contact the Department of Communication or one of our faculty.