Scholars in Michigan State University’s GEL and LiTL Labs are leveraging XR technology to revolutionize how health care professionals are trained to care for patients with tracheostomies and laryngectomies.

Virtual reality meets health care

An exciting collaboration between Michigan State University’s Games for Entertainment and Learning (GEL) Lab and Lip-Tongue-Larynx (LiTL) Lab leverages VR in a surprising way.

Partnering with faculty experts from MSU’s speech-language pathology, nursing, and medical programs, the interdisciplinary team created an innovative VR curriculum to prepare health care professionals and students for the complexities of caring for patients with tracheostomies and laryngectomies.

This project, funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, is bridging the gap between the entertainment world’s cutting-edge technology and the medical field’s practical needs. The result: immersive, low-stakes training that enhances both learning outcomes and patient care.

Bridging disciplines

CSD Professor Jeff Searl directs the LiTL Lab and leads the project, called “Tracheostomy and Laryngectomy Care: Virtual Reality Training for Health Professionals” or TLC-VRC.

Searl explained how, for years, health care students have faced limited opportunities to work directly with tracheostomy or laryngectomy patients. These procedures, which are often required due to cancer or other serious conditions, involve significant alterations to patients’ airways — impacting their ability to breathe, swallow and communicate.

Despite the critical importance of managing these cases correctly, the existing training options — a combination of textbooks, videos and hands-on learning during clinical rotations — do not always provide the depth of knowledge students need. Many health care providers, including experienced physicians, can also lack confidence in working with these patients.

“The likelihood that [medical students] would actually get very much patient exposure to these kinds of unique groups of patients, like those with trach or a laryngectomy, is relatively small,” Searl said. “The other issue is, we basically have patients that become the learning ground for our students. And that’s not always great if your very first learning experience is on a live person — especially when it’s a delicate procedure that you’re doing that has the potential to create at least psychological discomfort, and maybe actual discomfort and pain.” Searl noted that in more extreme situations, care providers can cause a serious health problem for the patients that they’re trying to treat.

The VR curriculum aims to address this gap by providing learners with a virtual simulation where they can interact with patients in a realistic, controlled environment without the risk of harming real people.

To do that, Searl needed to call in another kind of expert.

Enter the GEL Lab, led by experienced game designers Professor Brian Winn and Professor of Practice Andrew Dennis. After all, the same game engines used to create immersive experiences in entertainment, like Unreal Engine or Unity, are also key to creating realistic VR simulations for health care.

To replicate the immersive feeling of a real-life medical scenario, VR requires high fidelity in both visuals and interactivity, all while maintaining a smooth 90 frames per second to prevent motion sickness.

“We’re trying to make it as real and as good-looking as possible,” said Dennis, who is a co-investigator on the TLC-VRC project. “There’s all the modeling, all the things that go into it ... but with the stuff that I teach, there’s the added challenge: it has to work in real-time.”

Kathryn Genoa-Obradovich, M.S., CCC-SLP, a Ph.D. candidate and clinician, described how working on this project has fostered connections across departments, bringing together disciplines that traditionally have little overlap. “It’s so cool to be able to work with the game design students and to get to know them and their realm of study and expertise. I would have never been able to collaborate with them without this,” she said. “From what I’ve witnessed, they seemed to be similarly excited. Having students wanting to learn about what we do… and some even considering maybe pursuing a doctorate in our field because they were now exposed to it, and are like, ‘Whoa, here’s how I can blend engineering with coding with game design.’”

Building a VR curriculum to solve real-world health care problems

From the start, this project has been a gratifying experience for Dennis, who noticed an industry-wide decline in approved grants for VR and game projects due to many projects failing to develop — at least, not the way professional game designers can.

“Making a game is very difficult,” Dennis acknowledged. “I think it turned a lot of funding agencies away from games for a while, too, because they would give grants for people to make games and they would not deliver — because everyone learns, wow, it is way harder than you think.”

Fortunately, the GEL team was prepared for the challenge.

“We got a small amount of money through the startup funds to develop a functional prototype to show it could be done,” Dennis explained. “That led us to a slightly larger grant from Trifecta to keep developing it. That built us a pretty robust prototype that we then took to the National Institute for Health for their cancer project — and I thought that was one of the best things we did,” he said.

“That prototype … when we went to them, they could see it, they knew it existed. They knew we had the capabilities of making what we described. We weren’t just describing something we wanted to do; we were describing expanding on something we had already done.”

From there, the curriculum development process was a multi-year effort, collaborating with Mary Kay Smith from The Learning and Assessment Center and College of Osteopathic Medicine, Peter LaPine from the Department of Communicative Sciences and Disorders, and Gayle Lourens from MSU’s College of Nursing. Dennis’s team at the GEL Lab worked closely with health care faculty and graduate students throughout the summer months, creating various modules and refining the VR experience based on their feedback.

“Week by week, we would feed them information and content, and they’d say yes, we can do that or no, we can’t,” Searl explained. This back-and-forth process helped ensure that the final product would be both medically accurate and easy for students to navigate.

Genoa-Obradovich took the VR immersion one step further — even getting into a motion capture suit herself to simulate patient movements. “There are certain things that would be tricky to try to emulate unless you’re familiar with the population,” she said. “As a clinician, I’m the one who would kind of know what they look like or how they’re responding. But then to have them strap you into all of these motion sensors, it’s really fun. That’s been exciting; you feel like you’re in a video game.”

As for the audio component, the team invited real patients to lend their voices to developing this curriculum. “To make it more realistic when the students are analyzing deficits or difficulties, or the simulated patient’s challenges or chief complaints, we’ve had some individuals record their voices for us,” Genoa-Obradovich said.

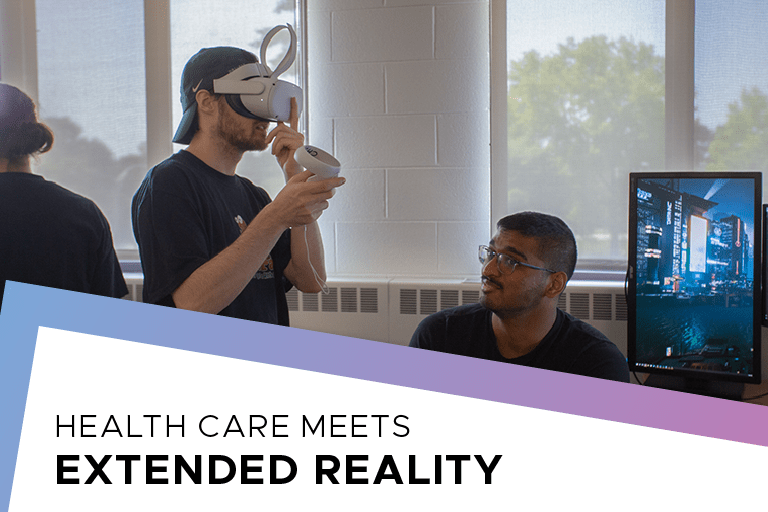

Photos: Students working on the TLC-VRC project in the GEL Lab.

The first module covers foundational knowledge, such as the anatomy of the neck and the differences between tracheostomies and laryngectomies. The second module includes a set of four patient cases in which learners work their way through different scenarios with those patients. All the while, students can interact with 3D models, assembling parts of the airway, familiarizing themselves with tools and supplies, and practicing procedures in a hands-on, immersive way.

Searl would like to see this curriculum made available as widely as possible. “What we really hope will happen is that training programs, like our own CSD department, or the College of Nursing or Medicine here, or anywhere around the world — that they would have an instructor who knows about the app and figures out a way to position it within their own curriculum, within their own training, wherever it’s going to fit best for them … And then actually have an instructor, or several instructors, who will lead students through the experience,” he said.

Otherwise, the team plans to make the VR modules freely available for download via the Meta App Store, allowing programs around the globe to incorporate the TLC-VRC curriculum into their training.

Forward thinking

Looking ahead, the team at the GEL Lab see even broader applications for VR in education and health care, including mental health support.

The GEL Lab encourages project leads to contact them about including game or XR development in research proposals, as developing interactive simulations that can serve as training tools or educational platforms is what they do best.

“It’s kind of fun to work with the students and the VR team because they have some ideas about how to gamify things and make it fun and interesting,” Searl said.

Genoa-Obradovich agrees. “It’s really inspiring, but it’s also invigorating, working all together. You can feed off each other’s energy, which is nice,” she said. “Once I was exposed to VR, I immediately started to think about how to apply it to my patient populations, whether directly in therapy or with further training for students.”

“Most of the GEL Lab projects have been a partnership between us, who represent the expertise to craft and build games, including XR experiences, and other faculty at MSU who bring their own domain of expertise,” said Winn, director of the GEL Lab. “These sorts of partnerships give us a competitive advantage at MSU when pursuing grants. Collectively, we can design, develop and research to advance the field forward. This has definitely been the case when it comes to redefining education and collaboration using XR.”

By Jessica Mussell

Research and collaboration

From exploring the psychology of virtual interactions to building cutting-edge simulations that bring complex concepts to life, ComArtSci labs invite educators and researchers to join them in their mission. If you are interested in game or VR development in your next grant proposal, please request consultation from the GEL Lab in the early stages of planning.