The current study examined the effects of school closure during the COVID-19 pandemic through a survey of schoolteachers. Exploring the response of school districts and teachers is an important step in developing plans that will support learning/teaching during the upcoming academic year, while protecting the health and well-being of students and teachers

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization had declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic. {2} Across the United States, universities and schools ended in-person classes for what would be the remainder of the school year in all but a few states. {1} In response, many school districts moved their classrooms online with little time for preparation.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the effect of the closure of schools on a sample of U.S. teachers. Included in this study was an exploration of the educational response, whether mandated from the top down or personally initiated, and the support given to adjust teaching methods. Investigating the educational response to COVID-19 is crucial to prepare policy that supports learning while protecting the health and well-being of students and teachers.

Methods

This report is part of a larger investigation conducted by the Teachers4Research (coordinated the Voice Acoustics and Biomechanics Laboratory at the College of Communication Arts and Sciences at Michigan State University, in collaboration with members of the McKay School of Education at Brigham Young University). A 30-item survey of the effects of COVID-19 on teaching and vocal health was developed. The questionnaire contained a section about: [1] work details (e.g. grade taught, topics, response time, modifications), [2] online delivery details (e.g. tools, access, connections), and [3] life impact (e.g. stress, health, relationships). Participants for this survey were recruited using the Teachers Research Registry, a database of teachers from across the country who have expressed interest in participating in teacher-related research. Teachers were recruited for the database through outreach via email and educational listservs. The survey was distributed to about 2500 teachers in April 2020.

Results

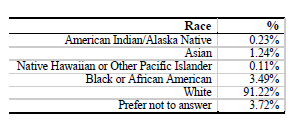

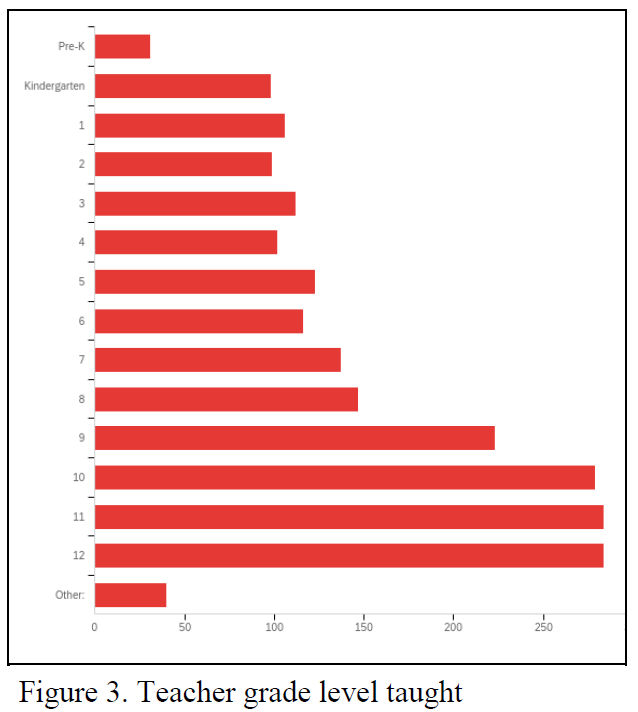

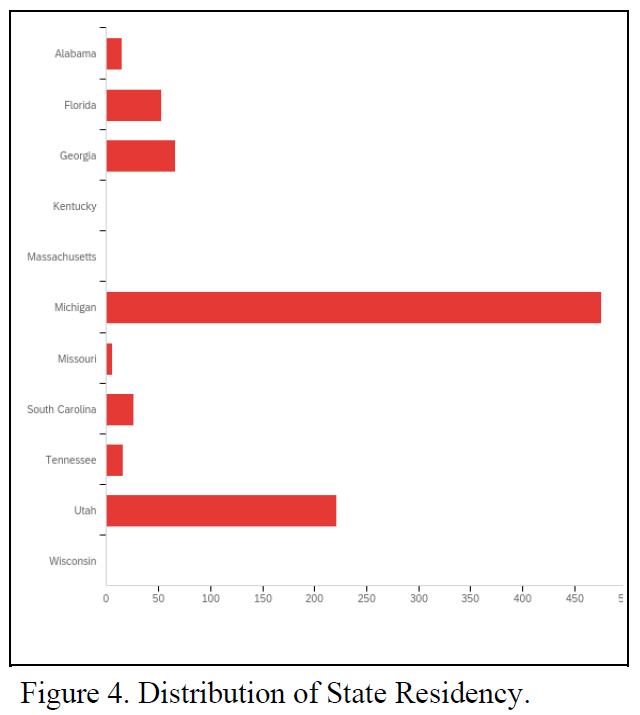

In a 3-week time span, 882 teachers from 10 states completed the survey, with respondents primarily coming from Michigan or Utah (avg. 44.43 years, stdev: 10.6 yrs; female 78.7%, male 20.6%). Table 1 details the racial demographics of participants. While analysis of the responses is still ongoing, a few highlights are presented below.

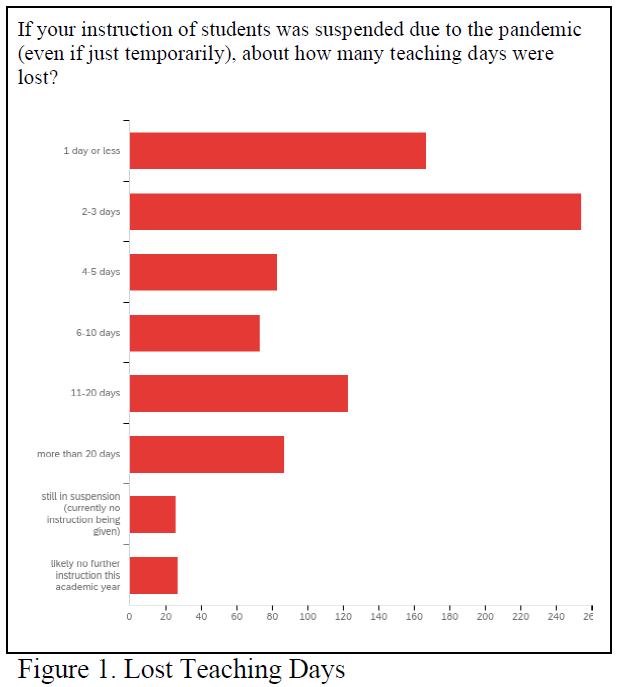

Loss Teaching Days

When asked about lost teaching days due to the pandemic, almost half of participants reported having already lost between 2-10 teaching days due to the pandemic. Additionally, nearly 2 in 10 teachers reported losing 20 or more teaching days and expected to complete no further instruction during the schoolyear.

Modified Instruction

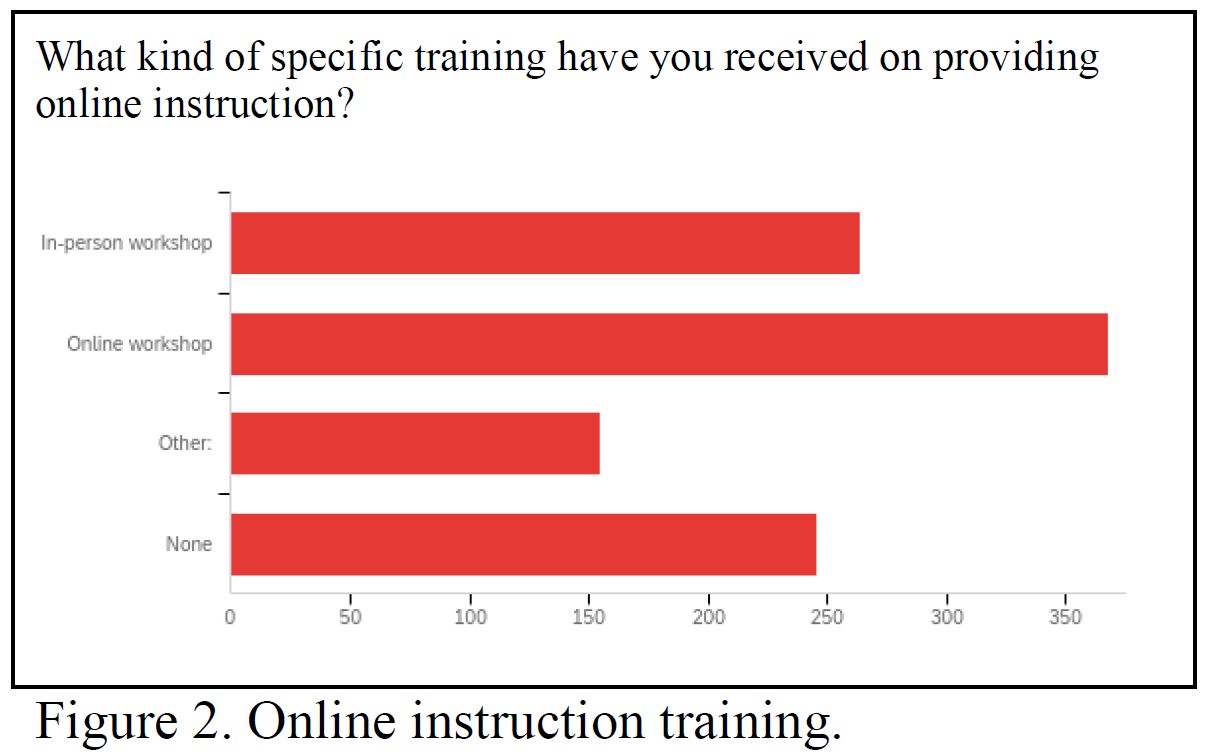

Due to the pandemic, many schools attempted to modify content delivery, with a variety of delivery methods including online delivery (with synchronous and asynchronous content) and delivery of hard copies of materials. The teachers were required to make this modification in a very short time span in most cases, with 66% reporting they were given less than 3 days notification before needing to provide modified content and nearly 75% had to completely overall lesson plans. While 90% of teachers reported that needed to deliver online content, nearly 25% had been given no instruction on providing online instruction and nearly 50% had never provided online content prior to the pandemic. Teachers have a higher than average incidence of voice problems due to heavy voice demands of teaching {3}; early analysis indicates that moving to modified instruction has increased the sense of vocal effort in more than 10% of the teachers.

Summary

Teachers and students lost valuable educational time during the pandemic. Those without knowledge of online delivery or access to adequate resources, along with those with students without appropriate access to needed technology, found themselves disadvantaged. Some teachers were unable to perform basic tasks, like giving instruction or helping with homework. Many parents were unable to support their children’s switch to online schooling (e.g. multiple children, inadequate subject knowledge, work demands).

A potential implication that could arise is that students will be behind in their schooling when in-person schooling begins, adding stress to teachers who will have to make up previous missed material while still reaching curriculum requirements for the current year.

References

1. Map: Coronavirus and School Closures. (2020, June 16). Retrieved June 26, 2020, from https://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/map-coronavirus-and-school-closures.html

2. "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020". World Health Organization. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 25 June, 2020.

3. “Gender differences affecting vocal health of women in vocally demanding careers,” Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 36, 128–136. Hunter, E. J., Tanner, K., and Smith, M. E. (2011).

Additional Demographic details

By Paige K. Dotson, Eric J. Hunter, Pamela R. Hallam

Paige K Dotson is a student in the Master of Arts program in Health and Risk Communication and working as a graduate research assistant in the Voice Biomechanics and Acoustics Lab: https://comartsci.msu.edu/hrcma

Eric J. Hunter, PhD is the Associate Dean for Research at the College of Communication Arts and Sciences at Michigan State University

Pamela R. Hallam, EdD is the Chair of the Educational Leadership and Foundations program at the McKay School of Education at Brigham Young University: https://education.byu.edu/directory/view/pamela-hallam