Mandy Hampton Wray started her academic career determined to find the cure to cancer. With a focus on biomedical research, she enjoyed the complex questions her research brought and looking for the hidden answers. But, the sterile environment of the labs she worked in didn’t mesh with her desire to interact with, and help, people.

In her undergraduate studies at the University of Texas, she took a brain and language class and found her calling, quickly changing her major from Chemistry to Communicative Sciences and Disorders. She hasn’t looked back since.

Though the researcher hasn’t gone down in history for finding “the cure”, she has found a way to mix her love of science with helping those in need by studying the complex speech disorder known as stuttering.

A Focus on Stuttering

These days, Hampton Wray is on a path to discover some of the brain bases behind why people stutter. As an Assistant Professor in the Communicative Sciences and Disorders Department at the College of Communication Arts and Sciences, she is currently collecting longitudinal data to try to answer some of these questions.

Her focus is on the development of brain systems for language and attention in young children, studying the ways in which development differs in children who stutter versus those who don’t. Her goal is to help shape the way clinicians treat the disorder and discover why some children persist while others recover.

Mandy's test subject Maddy, wearing an electrode cap and keeping busy.

“Hopefully in the next 6 to 12 months, we’ll be able to look at the current data we’ve collected of young children aged 3 to 5 and see if there are differences between children who stutter and children who don’t stutter in selective attention or inhibition skills,” said Hampton Wray.

Working in partnership with Dr. Soo Eun Chang, a former MSU professor who now works for the University of Michigan, Hampton Wray does not know of any other researchers looking at the brain functions for attention and self-regulation in children who stutter.

Studying the Brain

In her lab at Michigan State University, Hampton Wray studies the brains of young children using electrode caps, a stretchy cap with wires and electrodes that sits on the scalp of the participant and records the electric currents of the brain. The cap is plugged into an amplifier that transmits to a computer, which records the brain’s activity.

“We’re recording the brain’s response to stimuli - pictures, words, sentences - and we can see the brain’s response to the stimuli by time-locking the presentation of the stimuli to the brain’s electrical activity,” said Hampton Wray. “So when you see a picture, we can know when that picture was shown and how your brain responded to that picture.”

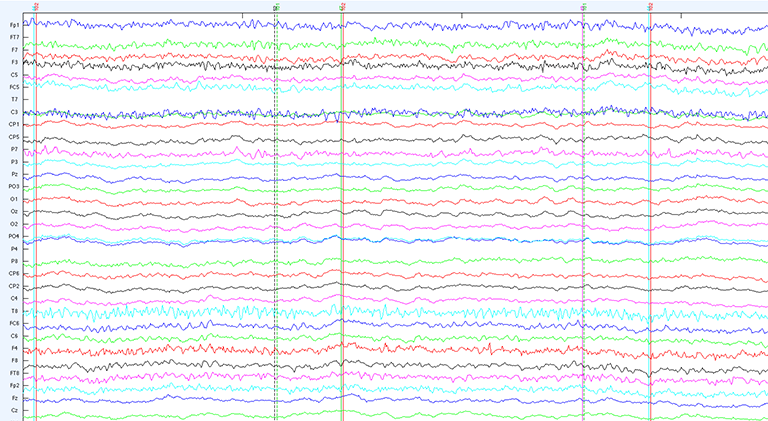

Example of the data Mandy reviews for her studies.

With a knack for keeping four-year-olds involved using colorful, engaging images, Hampton Wray is able to get the data she needs. The squiggly lines recorded from the brain tell her when a child was engaged and how they processed the information they saw or heard.

“If we can collect data across five years that’s ideal because we can track how children’s brain functions change over time, which is a really rich way of understanding development,” said Hampton Wray. “Statistically the groups may be different, but there is a lot of overlap in the middle. Who are these kids that look the same as one another but have different diagnoses? Those are the other questions to be answered in the future.”

Through this snapshot in time, the researchers will be able to look back at the data and determine when a child’s brain began to change. The information will allow them to answer a burning question in the field of stuttering research - are there noticeable patterns of development in kids who persist versus kids who recover?

The Road to Recovery

After five years, the team hopes to have the answer. Long term, the research can help clinicians to better understand the differences between the children who look the same at first but who ultimately have different trajectories.

Hampton Wray notes that about three-quarters of the young children who stutter will recover, while one-quarter of the children will continue to stutter into adolescence and possibly adulthood.

Mandy Hampton Wray with her electrode caps.

Right now, there are few ways to predict whether a child will persist or recover from their stutter. Males are more likely to persist than females, for example, but Hampton Wray says that’s a broad prediction factor. Also, if people have a family history of stuttering, and of persistent stuttering in particular, it’s more likely that they will persist than recover.

“But that’s only about 50 or 60 percent of people, so that’s a pretty general measure,” said Hampton Wray. “We’re hoping to be able to develop a more refined predictive formula. Then ideally we can do better diagnoses early on.”

These factors would allow clinicians to better target their therapy efforts to help the kids who need it the most, at the most critical time period. As it stands now, because 75 to 80 percent of children will recover, many clinicians take a “wait and see” approach to care. But, for the children who persist, that’s wasted time when they could have started therapy.

“The younger you get therapy services, usually the better it is,” said Hampton Wray. “So if we can predict more accurately when kids are really young, then those kids can get services when they need them the most.”

Filling the Gaps

In addition to the data the team acquires from their research at MSU, they are also collaborating with researchers at Purdue University who have been working on a large stuttering project since the mid-eighties, but specifically focusing on children for the past 10 years.

“They’ve collected a lot of data from children who stutter as well. So we’re looking at our own data, specifically at attention and inhibition, but we’re also looking at data that’s been collected looking at language development and some other aspects of cognitive development,” said Hampton Wray.

The research team plans to use the information from both studies to help fill in some of the gaps related to why children develop stuttering, as well as the methods that are most beneficial for treatment.

Doing What She Loves

After discovering her passion for speech sciences, Hampton Wray began her career working at Purdue University with Dr. Christine Weber on the Purdue Stuttering Project. She gained her master’s degree from the university and soon after, her Ph.D., beginning a journey into the career she loves.

Mandy Hampton Wray in her lab reviewing brain activity.

“I always knew, as soon as I started my master’s thesis, that I love this, I have to do this forever, ” said Hampton Wray. “My passion was always in research. I like the clinical aspect of the field. I think it’s critically important and clinicians do incredible things, but my passion lies in the research aspect and trying to find some answers.”

Hampton Wray completed her postdoctoral training at the University of Oregon, which soon lead her to her current role at Michigan State. Now in her fourth year, she is well on her way to growing the field of stuttering research.

“I love MSU. This department is vibrant and exciting. It makes for a really fun to place to work,” said Hampton Wray. “The students want to be here, the faculty want to be here. It’s exciting to have fresh voices and new ideas and innovative ways of doing things that may not have been done before. This keeps things exciting and moving forward in a really nice direction.”

By Nikki W. O’Meara